Lesson: Islamic Gardens

Name: Mary Mark Munday

School: Maryland Institute College of Art, Young People’s Studio; Center for Art Education faculty, Charles Carroll Elementary School

Programs: Cultures in Clay, grades 3-8

Discipline/grade level: Art, grades 1-5

Rationale: As one would travel through an Islamic garden, exploring its parts, marveling at the individual design elements and comprehending the parts-to-whole, so the progression of this unit can be used. The first lessons could be used with elementary participants and successive lessons for older participants, or all can be a small introductory course in all aspects of the Islamic Garden. This, lesson 5, is the end of the garden path, the site of still water - the reflecting pool.

Using knowledge and practice of geometry, participants design and build substantial clay vessels to hold a pool of water and clay elements that are designed, built and arranged to be reflected in the water. The theme of this lesson is The Self, expressed in visual symbolic form and pattern as elements to be reflected in the water. The resulting artwork is viewed as one - object and reflection

Grade Levels: Intended for grades 5 – 12 and adults. The last lesson in a unit of lessons-as-journey through “Islamic garden” themes, lesson 5 explores the concept of self. Aspects of one’s self are often made visible through the unique processes and choices for art making. Reflection itself is a double entendre in this lesson - both the product and the desired activity after making.

Time: Lesson 5 needs three 2-hour studio periods or six 1-hour studio periods from start to finished glazed piece. Add at least a week after the wet clay is completed to let the clay dry and bisque-fired. Then the last two-hour period allows for work to be glazed for final firing.

Disciplines: Besides Visual Art, some lessons in this unit can be adapted for Social Studies, Math, History, or Language Arts, where access to art materials might be limited. Paper collage as well as drawing can be used for mapping and planning garden ideas. Making journals, postcards, and brochure-type publications can be vehicles for individual plant and animal studies, comparative history of garden culture, and writing and design components.

Big Ideas: The flow of ideas across borders through time.

Ideas and Form

Part I: Making a Pool

Warm up: Participants sit around teacher prototypes of pools. Write and sketch what you see.

Discussion: Looking at photographs of reflecting pools, students will list ones they know (DC Mall) and compare/contrast them to Islamic examples; discuss experiences at such places (restful, contemplative) or what it might be like; why these might have been important.

What do we have in our busy lives to help us to get in touch with ourselves?

At this point participants will only concentrate on the engineering and design of the water pool vessel. Later parts of this lesson will ask them to think about what shapes and forms translate to symbols of self.Demonstration: Rolling clay slabs, drape-molding curved or rectilinear forms, designing and building upside down to make the pools stationary, joining clay to facilitate adding on any “platforms” or generic side extensions.

Studio: While clay is setting up, or if some participants finish before others, they will begin to draw a projected view of their pool as they imagine it finished.

Assessment: Participants will be asked to take a gallery walk and look for qualities of craftsmanship in joining and finishing the building work. They will need to make direct connections from their work back to exemples we looked at.

Part II: Self-Reflection

Warm up: Participants complete a worksheet asking specific questions about themselves.

Reading: Excerpts from Conference of Birds

Visuals: Paintings from the Manuscript, other Persian garden miniatures, textiles

Discussion: Symbolism in Islamic garden imagery. Exemples from paintings and textiles.

Studio: Participants sketch plans for the reflective objects in their pools

Sharing/ Critique: Participants try to “read” the examples in each other’s sketches. PQP (Praise, Question, Polish) can be used to respond to each other.

Demonstration/Review: Geometric forms in clay and how to model from them.

Studio: Participants begin to model and apply the reflective elements to their pool vessels.

Assessment: Participants revert to previous sketches and write about how they modified and improved their ideas.

Cleanup: Again clay needs to be wrapped for final finishing work before firing.

Part III: Refinement and Elaboration

Warm up: Participants examine fired clay examples of proper joining and finishing, as well as pieces that have been deliberately poorly finished.

Discussion: What is the difference in these pieces? How can you achieve it?

Demonstration: Finishing clay so that seams are strong, surface areas to be handled are free of clay blobs that nick hands when fired.

Studio: Participants add any final pieces and refine their work

Demonstration: Surface texture using tools and stamping materials. Contrast between smooth and textured areas

Studio: Participants apply texture to selected areas of work.

Assessment: Participants share how their ideas and designs changed over the course of this stage of work. At this time the work will need to dry to be fired. Interim class period could be spent exploring Islamic poetry, especially the symbolic language of garden poetry.

Part IV: Color

Warm up: Participants list all the colors they see in the visual exemples.

Discussion: What kind of colors reflect under water and why? What kinds of colors reflect themselves in the objects “on shore”?

Studio: Participants make a sketch of their pools adding color

Demonstration: Applying Glazes or Underglazes

Studio: Students apply glazes to be fired

Assessment: Students check each other’s work for craftsmanship in applying glazes.

Final Assessment of Finished Work: Students fill vessels with water. Each one may take several digital photos of the reflections to be used for an “artist’s statement” to accompany the work. The photo will be displayed with a poem the student writes in response to the work. The poem should reflect the style of Islamic poetry that is fairly short and allegorical (e.g. Ghazal).

This lesson is part four of a larger unit, detailed below.

“The mission of the Prophet Muhammad led to the establishment of Islam as a religion and a state, which was confined to Arabia during the Prophet’s lifetime. After his death in AD 632, Islam grew rapidly to encompass a vast area that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indus River in what is now Pakistan. In the tenth century this great empire disintegrated and new forms of political authority emerged. Nevertheless, until the early twentieth century all the states that succeeded the first Islamic empire were based on Islamic law and beliefs.

In the Islamic Middle East, as elsewhere, patronage

followed power, and the ruling elite set the style in artistic production.

Yet the people who commissioned, designed, and made this art were not

all Muslims. Nor was the content of Islamic art necessarily

religious, since it also reflected a sophisticated secular culture. ‘Islamic

art’ is therefore a broad cultural term rather than one based

on an exclusively religious definition.”

-- Tim Stanley, Senior Curator, Middle East Asian Department, Victoria

and Albert Museum, 2004

Millennia earlier, geography and the environment itself unified what would become the Islamic world by the constraints of living environment. The earliest inhabitants in land predominated by rock, dust, and harsh heat quickly sought the shelter of valleys and oases nourished by springs and shaded by trees. It wasn’t long before settled domains of power could demand engineering and labor to build such havens. Writings chronicling the time of Solomon mention his elaborate raised gardens as well as those of Babylon and Egypt. The idea of garden was not new to the Islamic world but the “network of Islam” with its vast trading activity helped to spread the garden in its most significant form to Italy and the rest of Renaissance Europe.

Imagine that as far as you can see there is a landscape of brown and grey rock, dusty plateaux, and more brown and grey mountains. The sun is hot, reflecting the heat from this barren surface all day. But just behind the wall lies the garden with its cool avenues of shady trees, beds of colorful fragrant flowers, trees bearing fruits, and brooks with water flowing constantly. Cool, shady, lush, colorful, soothing in contrast to the wasteland outside. It was a Central Asian Nomad’s dream of Paradise.

Thus it was also common to find “resplendent gardens” woven into carpets to cover floors of tents and houses. It was in the weaver’s environment that we find the designs and motivation.

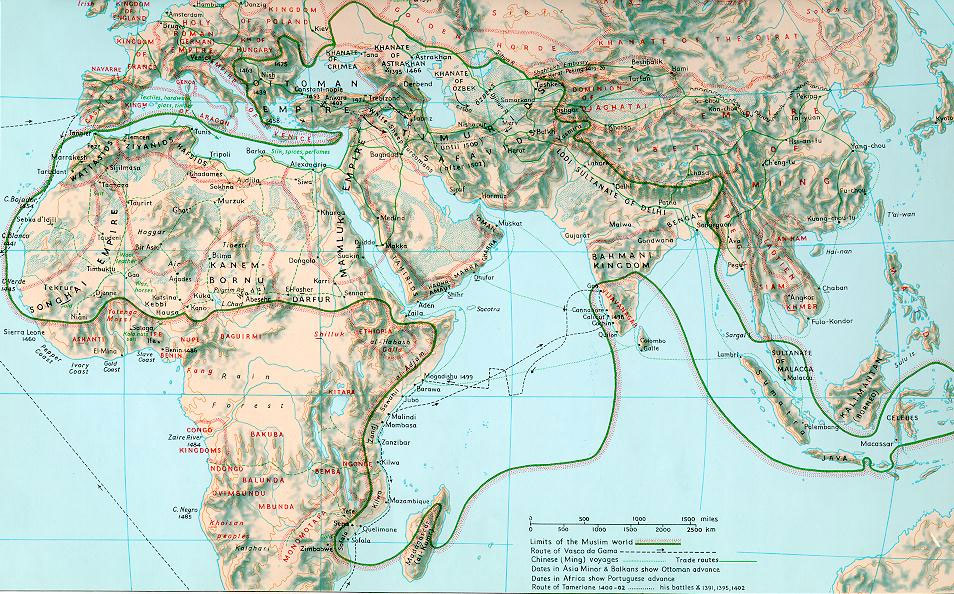

In the 14th century, Timur (Tamerlane) ruled most of Eurasia, the area from east Europe to China. He brought thousands of artists to his capital, Samarkand, and built and decorated fabulous Mosques. However, he never built a palace. He remained a tent-dweller, a Steppe nomad, till he died. But he did build nine gardens that surrounded his tent.

Verbal to Visual

The sacred aura of the garden was enshrined in the Koran where the faithful

are promised a Paradise “of gardens beneath which waters flow.”

The descriptions here probably inspired later artists using garden design

in textiles and paintings.

Sacred Space, Earthly Paradise, Secular Ritual

Garden and Courtyard are important forms in the concept of Paradise (Bagh/Hayat).

Specific gardens were designed for specific purposes.

A symbolic spiritual Paradise

This was the purpose of the garden designed by the Qajar ruler of Iran.

In 1797 he built Qasr-i-Qajar in Tehran. It had three main areas symbolizing

the ancient Iranian cosmological model, based on the idea of a colossal

mountain, Sad Matati (great mountain of lands) that lies across the sea

towards the North. The northern part of Qasr-I-Qajar was a 5-tiered garden

on a rocky cliff with an elevated fortress housing a quadripartite garden

like the Garden of Paradise in the Koran. Below the cliff, an enormous

shallow water basin called “the Ocean” separated the third

southern area of the flat canals that irrigated the rectangular flowerbeds

and orchards. This represented the fertile landscape of the Iranian plateau.

Pleasure Garden of Fragrance and Light

At the Palace of Amber, Rajisthan, India there is a “Night Garden”

called Maunbari. Because color is lost at night and no trees are needed

for shade walls, one foot high, in ornate shapes and patterns, divide

beds of white flowers which bloom at night giving off a wonderful fragrance.

Water is channeled over a wall perforated with one hundred niches. From

behind the wall, servants place lamps in the niches. The effect at night

is of luminous shimmery stars.

Garden Choreography for State Ritual

The Bari Mahal, built in 1698 at Udaipur, Rajisthan, was the throne area

of the Maharana, who would summon his nobles to court there so that the

proclamation of edicts, decrees, and justice were given in the context

of a mythical garden. Emperor Akbar’s throne at the Fatehpur –

Sikri palace was an actual stone tree. He would sit high above the heads

of his court, out of sight even, and “finally and irrevocably like

the fabled bird in the tree of life,” issue his decrees.

Trees

Symbol of wisdom; roots in meditation; bears fruit of spirit.

“Tree of life” is seen as the connecting link between the

three world levels of the ancient Orient: Paradise (sky), World of humans

(Earth), and the World below.

Fruit trees: apple, pomegranate (symbol of fertility – land, nature,

humans); fig (also symbol of fertility)

Cyprus (sacred to Apollo as god of light in the Classical world; used

to represent light on graves, mausoleums)

Flowers and Shrubs

Roses, Tulips, Jasmine, Chrysanthemum, Lilies; used for color and had

own symbolism. Some plants were chosen for their fragrance. White plants

and night-blooming plants were used in gardens to be seen at night.

Birds

Their language is the symbolic language of self. This language of birds

in the human world is rhythmic language, and the science of rhythm was

thought to be the means for reaching a higher state of being.

Hoopoe – symbol of inspiration

Nightingale – self caught up in the exterior form of things

Water

Cooled the environment

Flowing water gardens were idealized forms of irrigation whose geometry

was used to design water pathways—an exercise in pattern making

Cascading water was made possible as different levels were built.

Natural springs, if found on site, could be used with hydraulic pressure

to channel water through fountains

Still water was used as a metaphor and to reflect buildings, trees, plants,

shrubs for added splendor.

Pathways and Divisions

The Persian word Pairi-daeza means walled space or enclosed area. It is

standard to have four quadrants or Chahar bagh to compose the proper garden

with pathways and, if possible, waterways that divide up the space and

lead one to a central area. This area may hold a courtyard, a pavilion,

or a fountain.

Timeline:

4000 BC |

900BC |

500BC |

800AD |

1400AD |

1795AD |

Mesopotamia Egypt Babylon |

Solomon |

Persia |

Spread of Islam and Gardens throughout Mughal

India |

Italian hanging garden craze |

Qasr – Qajar Tehran |

| Architecture Carpets Paintings |

Poetry Photographs |

Books:

Bakhtiar, Laleh. Sufi (Expressions of the Mystic Quest). London: Thames and Hudson, 1976. Richly illustrated information useful to all aspects of Islamic study; addresses symbolism and connections to everyday life.

Danby, Miles. Moorish Style. London: Phaedon Press Ltd., 1995. Although poorly titled this book provides the complete scope of Islamic culture through categorized big ideas: Roots, Space Elements, Pattern, etc. Stunning photographs.

Farid Ud-Din Attar; Davis, Dick (Translator); Darbandi, Afkhan (Translator). Conference of Birds. N.Y.: Penguin, 1984. ISBN 0140444343. 12th c. mystical poem – unabridged translation; new reissue of C.S. Nott’s classic prose translation; epic poem explores the nature of spiritual path through allegory of brave birds in search of their “king”. “We are these bird-beings searching for the source of what we are together.” – Coleman Barks

Ford, P.R.J. Oriental Carpet Design. London: Thames and Hudson, 1981. Especially useful: Chapter 3, pp.106 –117 Tree Designs; Chapter 6, pp.144 –155 Garden and Panel Designs; A wonderful overview of all carpet designs.

Hazelhurst, F. Hamilton. Gardens of Illusion (the Genius of Andre Le Nostre). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1980. Showcases the great garden building movement in Italy and France inspired by the gardens of the Islamic world.

Jones, Dalu (Ed.) A Mirror of Princes (The Mughals and the Medici). Bombay: Marg Publications, 1987. Clear parallels are drawn and illustrated between the Italian Renaissance trading Princes and the Mughal Princes of India. Clear exchange of ideas through painting, sculpture, architecture, furniture, and design.

Khonari, Mehdi; Moghtader, M.R.; Yavari, Minouch. The Persian Garden (Echoes of Paradise). Mage Pub. 2004. ISBN0-934211-75-2. Excellent comprehensive work on Persian gardens.

Websites:

http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~arch/181/persiangarden.html

http://isfahan.apu.ac.uk/persgard/index2.htm#intro

Keywords: Persian garden, Mughal garden, Persian painting

Makan – “place-making”, unifying all buildings by providing

basic contact with nature, so essential to Iranian life. Ex: the courtyard

in a home.

Nadir – (literally miracle) Nadir al Asr – Miracle of the

Age

Ogival – matrix of floral forms

Spandrel –

Components of this unit address all the outcomes:

Outcome I: Perceiving and Responding – Aesthetic Education

Demonstrate the ability to perceive, interpret, and respond to ideas,

experiences, and environment.

Outcome II: Historical, Cultural and Social Context

Demonstrate understanding of visual art as a basic aspect of history and

human experience.

Outcome III: Creative Expression and Production

Demonstrate ability to organize knowledge and ideas for expression in

production of art

Outcome IV: Aesthetics and Criticism

Demonstrate the ability to identify, analyze, and apply criteria for making

visual aesthetic judgements.

Lesson 1:

(Lessons 1 to 3 are here in outline sketch and will be completed

later. Lesson 4 is complete at this date.)

Mapping a garden

5 1-hour class periods

Observe examples of Islamic gardens, listen/read some poetry about the garden

Identify important components, their shapes and characteristics, and the kinds of patterns

Examine art forms (rugs, textiles, paintings) that portray garden layouts

Make a catalog of the variety of components with names, shapes, colors, features

trees

plants

birdspaths

waterways

courtyardsDesign and construct a garden map in the form of a tapestry or rug in any of these materials:

Paper collage

Colored pencil

Cloth appliquépainting

markersAssessment:

1.Rubric of components, pattern-making, symmetry, craftsmanship

2.Write a poem to one or more aspects of your garden

Lesson: (2 3 1-hour classes) Shah Jahan and his father Jahangir (India 17th c.) were Mughal rulers and also accomplished naturalists who made studies of plants and animals. Italian representatives from the Medicis visited India for trading purposes. The exchanges awakened each side to the marvels of each other’s lands.

Become an emissary from the Mughal court sent to the new world to document its natural wonders.

Develop a diary of sketches of local plants and animals around your school and home.

Pencil

Pen

Bookmakingcolored pencil

markers

colored ink(Readings, Exemplars, Assessment to be added)

Lesson 3: (2 1-hour classes) You have returned from the new world with a successful trading mission and wonderful images and notes. The new plants and landscape has inspired you to create a special motif for the new garden pavilion tile work.

Design a plant-inspired motif from your sketches that translates the new natural form into one more stylized in the Mughal tradition.

Use this motif to create a printmaking block and make prints of your design.

Extension: Develop this motif into one that can be printed in a rotating manner to repeat itself for larger areas.

Drawing, measuring, printmaking

(Assessment, exemplars, etc. forthcoming)